The Issei and Nisei Farmers: Their Legacy

Family Farm Histories

We are paying tribute to Issei and Nisei in the farming and agriculture industries (fishing, eggs, floral, nursery, etc.)

Our goal is to create the largest repository of JA farm histories so that our ancestors’ sacrifices and hard work will be recorded and never forgotten.

For questions, email walkthefarmlegacy@gmail.com

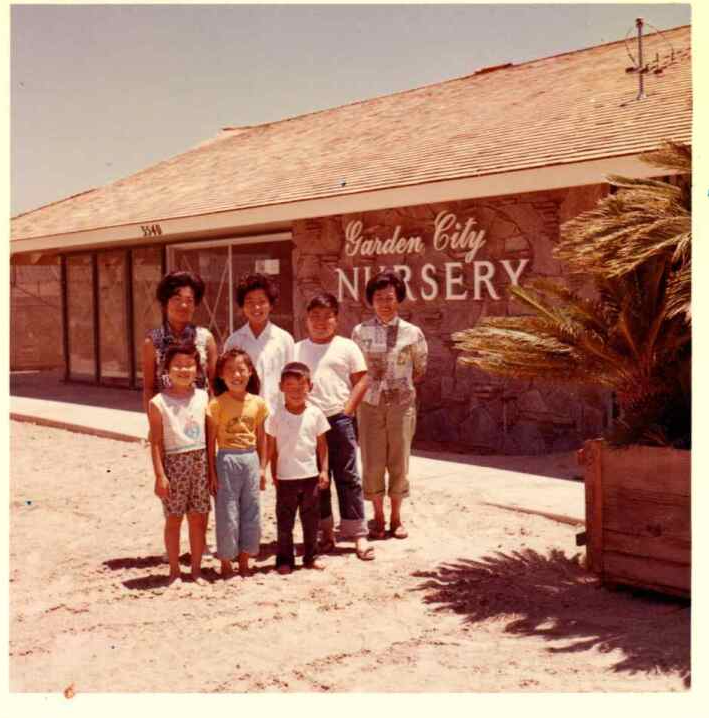

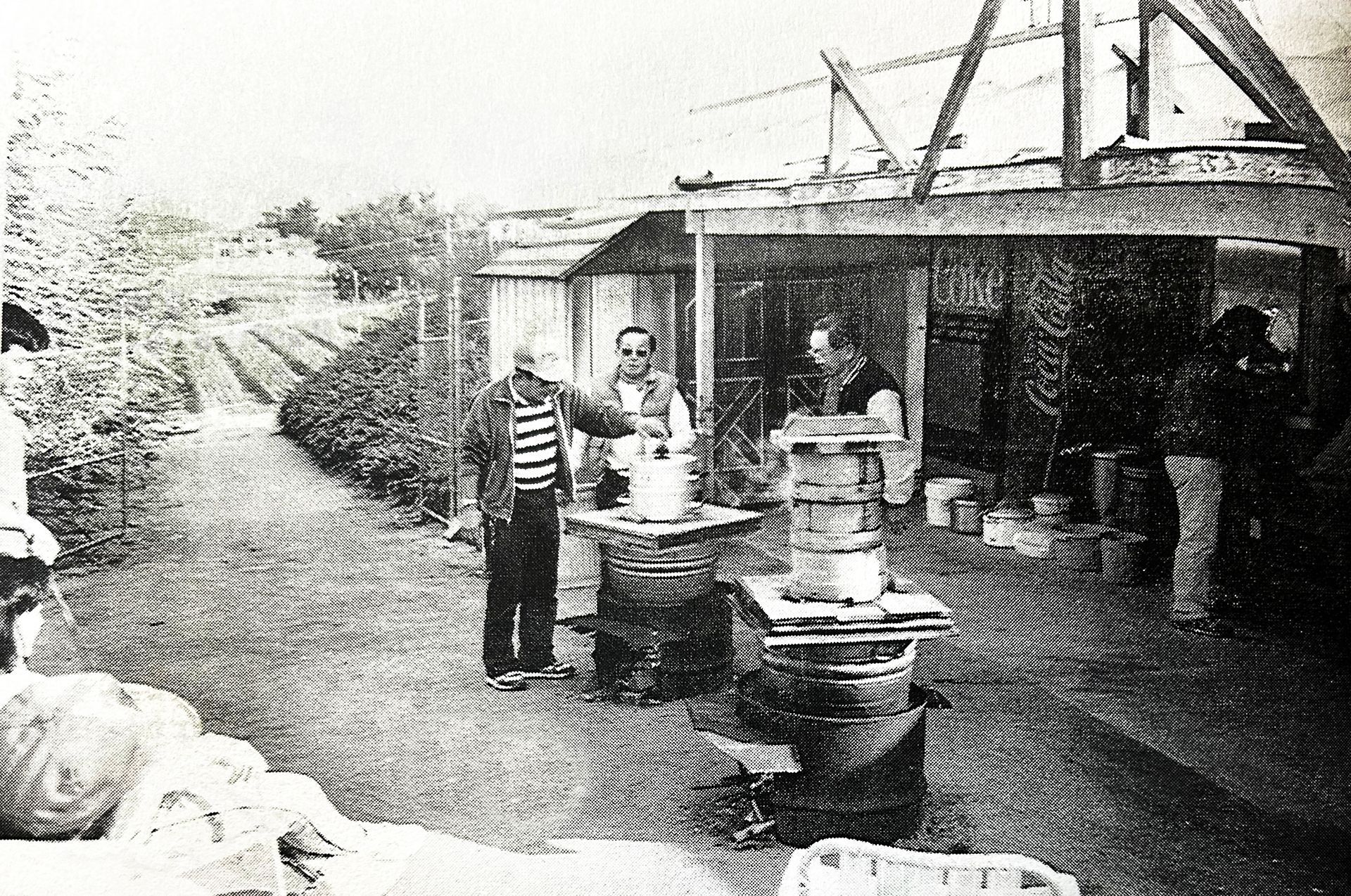

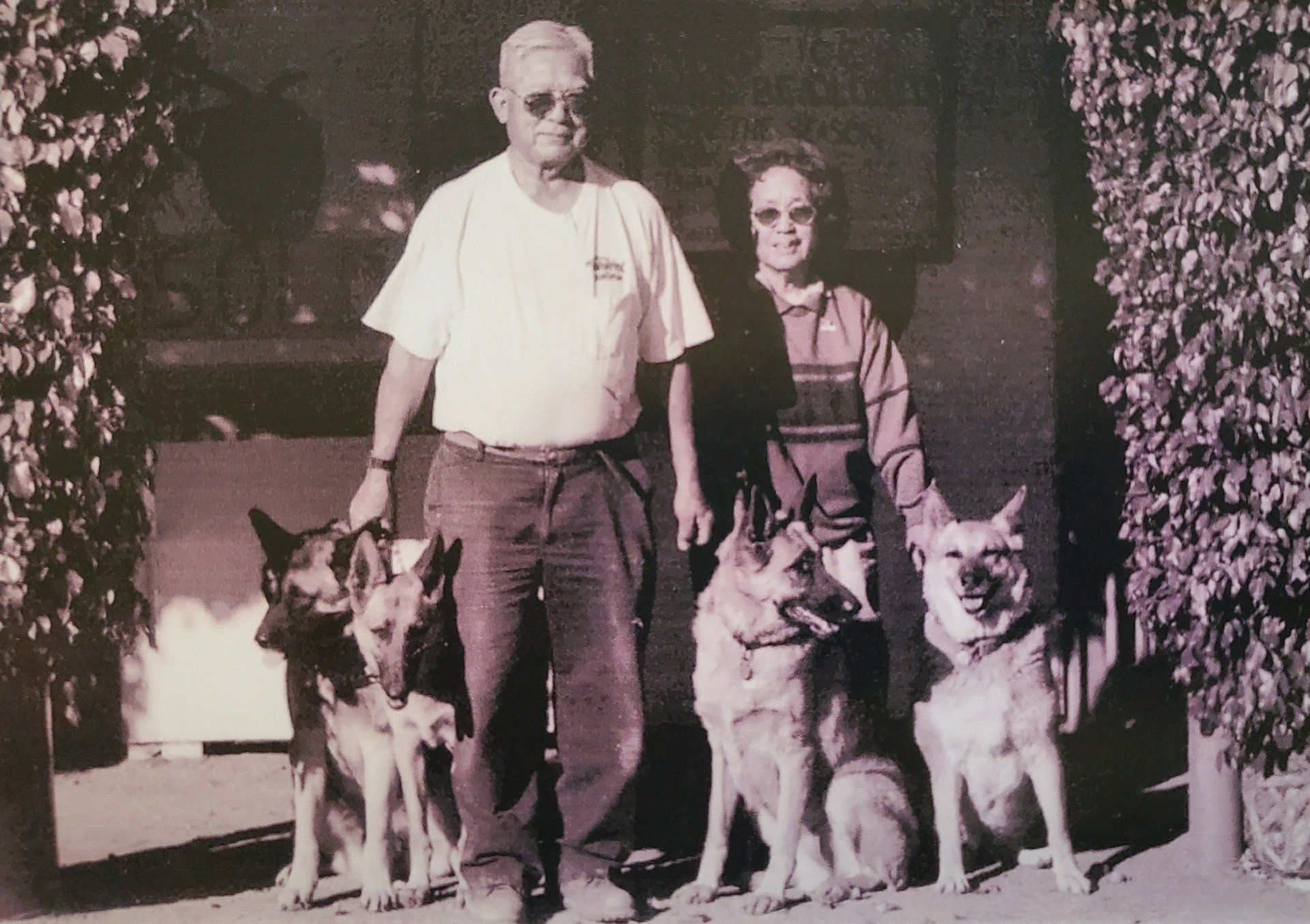

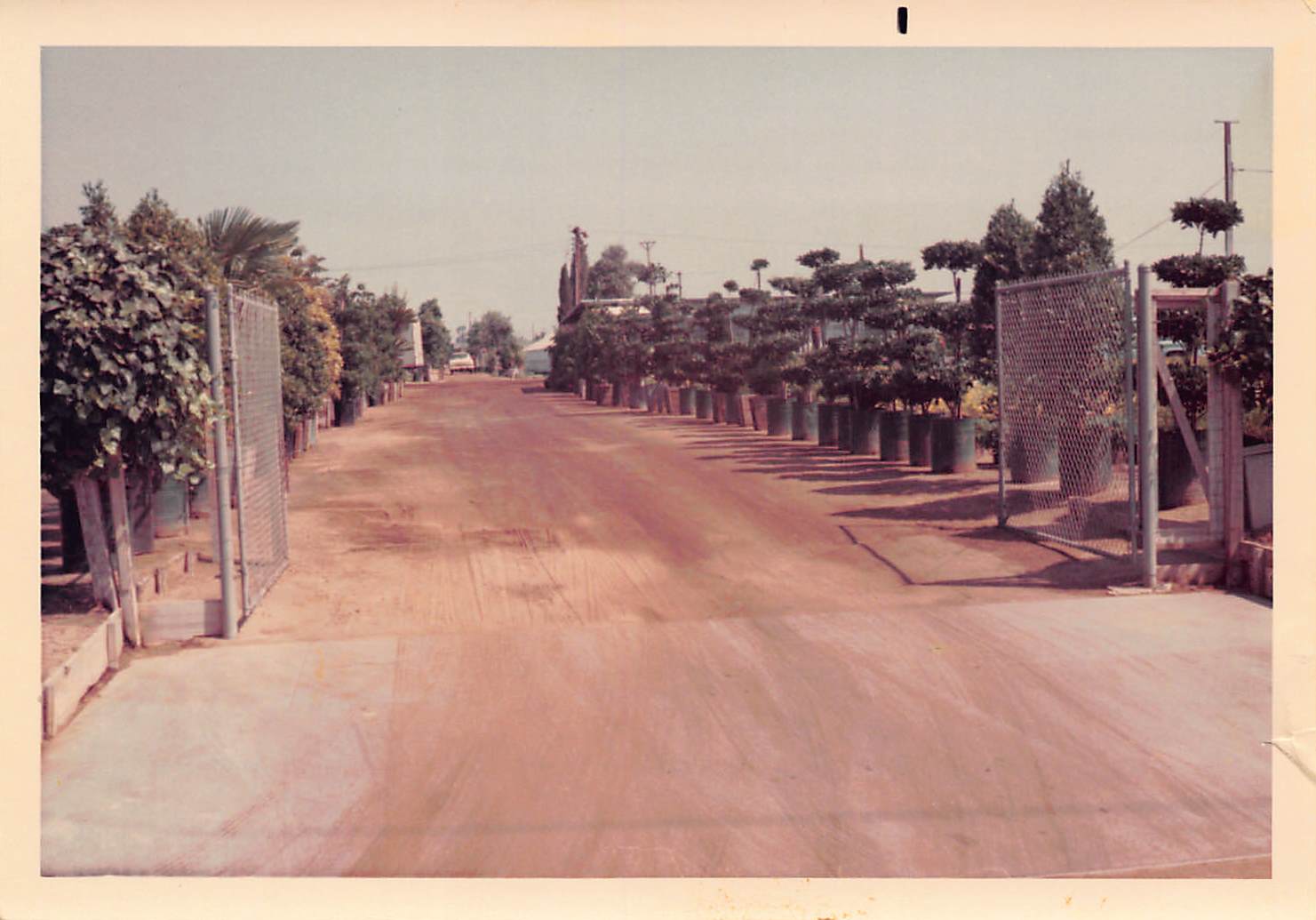

At the turn of the 20th century Yasaburo Hamada came to America from Jigozen, Hiroshima, at the age of 15. A man of small statue and a quick temper, “Harry” Hamada was adept in judo and kendo and was not afraid to use his skills. One family story recounts a job he had in San Francisco in the basement of a building. He argued with his boss and walked off the job. The next day the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake happened and buildings everywhere collapsed killing thousands including the people in the basement of Yasaburo’s building. At the age of 38, after more than twenty years in the U.S., Yasaburo returned to Hiroshima to find a wife. He was recommended to the beautiful youngest daughter of a prosperous farming family, Shiki Nagaoka. Shiki’s older sister had left several years earlier to marry a man in Hawai’i and she was also open to going to America. Shiki agreed to marry Yasaburo, 18 years her senior. She recalls the initial meeting he had with her father where she was expected to serve tea. Too afraid to even look at him, Shiki didn’t know what Yasaburo looked like until after she consented to marry him. They wed in Japan in 1920 and left for the U.S. soon after. Their son, Ben, was born in 1921 in Hollywood. Two more children followed, Namiye in 1923 and George in 1925. Ben recalls living in various places in Southern California: San Fernando Valley, Hollywood, San Pedro. They family worked hard at various endeavors but gravitated to farming and the nursery busines. Yasaburo, a man of many talents, had a gift for growing, not just plants, but animals too. Namiye remembers moving a lot but said they always had nice houses. The family spent the war years in internment camps, initially in Jerome, Arkansas, and later at Tule Lake, California, camp for the infamous “No-No Boys.” After the war, like everyone else coming out of camp, the Hamada’s worked hard to make a living. By then, Namiye was married to Manabu Okada who farmed with his brothers Taka and Shigeru. Yasaburo and Shiki had various jobs and 24-year-old Ben worked as a gardener, using trimmings to propagate new plants. Through their friends, the Gotos, who had a thriving flower shop in Montebello, the Hamada’s arranged to open a nursery next to the shop on Beverly Blvd, and called it Blossom City Nursery . Meanwhile, Ben who also wanted to farm, leased land in Huntington Beach on Talbert Ave. and Beach Blvd, while still helping his parents with Blossom City. By then he was married to Masako and they eventually had four children: Ellen, Ron, Kent and Joanne. The family’s nursery business was joined by George and his wife, Hazel, in 1950 when they returned from Chicago, baby Karen in tow, soon to be followed by Gerry, Teri and Parry. In 1953 the family purchased four acres in Garden Grove on Harbor Blvd and opened Garden City Nursery . The thriving business supported Ben and George’s families, Yasaburo and Shiki. They remained there until 1963 when the nursery was forced to move because of the construction of the Garden Grove Freeway. Garden City Nursery relocated to East Chapman Ave, Orange, in 1963. In 1971 brothers Ben and George parted ways and took ownership of separate properties and nurseries. George and Hazel continued operating Garden City and Ben and Masako opened Batavia Garden Nursery next to their home in Orange. Garden City Nursery closed in 1987. Batavia Garden Nursery remained in business until 2019, operated initially by Ben and Masako and and their children, Ron, Kent and Joanne.

In 1907 Takeo Sakuma left Kyushu, Japan to go to America. He moved to Bainbridge Island, west of Seattle and began farming; taking the ferry he sold produce at terminal markets and Pike’s Place Market. Returning to Japan, he married Nobu in 1914, immigrated in 1915 and they started a family. Takeo became known for strawberries, challenging due to growing conditions on Bainbridge Island. The fertile Skagit Valley near Burlington was recommended as ideal for strawberries. Atsusa Sakuma moved to Burlington in 1935. Atsusa was the oldest Nisei, first born in the U.S., and first to grow berries in Skagit Valley. One by one, Atsusa’s brothers moved to Skagit after high school to help with harvesting. In 1941 the brothers farming in Burlington supported the family remaining on Bainbridge Island. Then Pearl Harbor was attacked in December. The Sakuma family was imprisoned at Manzanar in March. In June the brothers from Burlington were ordered to Tule Lake (northern California), five hundred miles from the rest of the family. While family was treated as the enemy, three of eight Sakuma boys joined the famed 442 nd Infantry Regiment. Three other sons served with the MIS. After the war, the Sakuma family returned to Bainbridge, but their property was lost, so they moved to Burlington. During the war, their farm was maintained by the Oscar Mapes family—a never forgotten act of kindness. With success, the brothers went into the certified plant business in 1948. They provided the start for strawberry farmers throughout the West Coast. Two brothers in Redding, northern California, ran the growing Norcal Nursery around 1970. Norcal acreage covered Oregon and California. The Sansei generation started management from 1997 until 2000 when the last Nisei retired. Bryan, Glenn, and Richard managed Washington operations; Ron and John managed California operations. The Sakumas entered fruit processing in 1990, and Sakuma Brothers Processing, Inc. began in 1997. Since 1997, plant propagation, research, commercial operations and sales, berry and fruit farming, harvesting and beginning a fruit stand. Sakuma berries sell throughout the U.S. and worldwide. 2004 brought the first female board member and first Yonsei to the business. The tradition of excellence continues today. The new generation is committed as the first to their corporate vision: “Honoring our past, growing our future.”

In September 1903 at the age of 23 years, Juichi Nawa, the eldest son of nine siblings, left Gifu, Japan for America, arriving in San Francisco he worked for several years and by 1911 saved enough money to purchase ten acres of farmland in Norwalk, California. At the age of 19, Sakaye Okawa, one of eight siblings left Wakayama, Japan for America to marry Juichi in a marriage arranged by family and friends. On the Norwalk property they grew oranges, vegetables and raised chickens for eggs. They had four children, Jimmy, Mary, Stella and Jiro. Juichi and Sakaye were active in starting the Norwalk Gakuen, now the Southeast Japanese School Community Center in Norwalk. Life changed suddenly in April 1942 when the U.S. Department of Justice identified Juichi as a dangerous enemy alien and was detained at the Tuna Canyon Detention Center, Tujunga, California. In May 1942, unknown to his family he was transferred to the DOJ Internment Camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In August Juichi was reunited with his family at the Santa Anita Assembly Center and in September the Nawa family was transported to the Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas. Fortunately after the war ended the Nawa family was able to return to the Norwalk property. Starting over, they farmed and egg production became the primary family business again. Eventually, egg production gave way to a successful wholesale nursery business that lasted for many years. In 1977 the land was sold and within the residential area built on the property a street was named Nawa Lane.

Our Jichan Hisataro Nakagawa immigrated from Nukushina, Hiroshima, Japan to Olaa, ( Big Island, Hawaii ), when he was fourteen years old. He worked at the Kaiwiki Sugar Cane Company and in 1886, moved to the mainland of Bowles, CA. He obtained twenty acres of wine grapes. Hisataro, his wife Sasayo, sons Johnny and Dyna would run the farm from the turn of the century to the 1960’s. During WWII, The Nakagawa family entrusted their farm to neighbors and friends Jeppe and Alma Raven during their 'incarceration' at Jerome, Arkansas. After the war the Ravens picked up the Nakagawa’s from the train station and brought them back to their home and farm. Jeppe Raven gave our Jichan ( Grandfather ), Hisataro a cigar box. Inside was filled with the cash profits the farm made for four years! Not only did the Raven work the farm, they gave them back the profits too! Baseball has been in the Nakagawa family for five generations and Uncle Johnny was the Shohei Ohtani of the 1920's and 1930's. We feel very blessed to come from 'Earth People,' Baseball Ambassadors and great family cooks. Aloha and Mahalo Nui Loa from the Nakagawa family!

Like so many new arrivals of Japanese immigrants to the West Coast of the United States in the early 1900’s, Tomejiro and Kino Hoshino were no exception. Japan had sapped most its wealth financing the Sino-Russian war of 1904-1905. The rural and farming community suffered the most. Therefore, the Japanese government encouraged “kuchi herashi” (reducing mouths) and assisted these folks to immigrate to North America, South America and Hawaii for better opportunities. Tomejiro Hoshino, born 5/15/1887 in Sobue-cho, Aichi-Ken, left home and arrived with his older brother and his older brother’s friend in Mexico on 11/17/1906. When they came upon the Rio Grande River, the older two built a raft, enabling Tomejiro to cross into the United States as he could not swim. After struggling along the West Coast, Tomejiro found a job as a farmer in Elk Grove, California, and settled there. On 3/29/1915, he was able to send for his fiancee Kino Hattori to join him. The following year his first child Sakiko was born on 6/6/1916. In 1926, Tomejiro and Kino were able to purchase 20 acres located at Route 2, Box 2408, Elk Grove, Sacramento County, California, for $12,800 under their first-born daughter’s name (American citizen). This property consisted of a house, a warehouse, 8 acres of fruit trees, 2 acres of grapes and 10 acres of working fields. In 1939, registered owner of the land was transferred to their eldest son Jack Hoshino. That same year Jack entered the U.S. Army, and his sister Michi was given power of attorney. When war broke out in 1941, the entire family was sent to the concentration camp at Manzanar. The Hoshino property was left in the care of a neighboring farmer, but the annual property tax of $300 accumulated to $1,200 in 3 years. Unable to pay the tax, in 1943, the family had to let go of the farm for $4,100, one third of what they paid 17 years earlier in 1926. In 1951 upon his release from the Army, Jack sought compensation under a newly created law and received $2,500, a mere moral bandaid. Seven of Tomejiro and Kino’s children settled in Southern California with Jack being the exception, who elected to remain in Sturgis, South Dakota, where his army career ended. They all fondly remember the farming days. Though the work was hard and the world was cold and left bitter memories, the experience and discipline learned on the farm became a good foundation upon which to build their own families. None in the Hoshino family went into the agriculture field after the war. Elk Grove, where the Hoshino farm was located, has now become partially residential. That 20 acres purchased in 1926 for $12,800 is now valued around a million dollars. Yes, the prejudiced, unjust and uninformed did not help the Hoshinos during the Tomejiro-Kino era. All the descendants of the family feel very grateful for the sacrifices made by them and for the lives we enjoy today. Let us always remember! Now, it is our time to lend a helping hand to others toward creating a more just world.

Ichitaro Makishima sailed from Iwakuni, Yamaguchi-ken, Japan in 1896 at age 17 to work on a sugar cane plantation. But when he witnessed whippings, he ran away. Sixteen years later he was settled in Sacramento, California, and his mother sent him a bride. Twenty-year-old Yoneyo Makishima arrived in 1913. Ichitaro started a general store, and the family lived in a boarding house in town, but Yoneyo contracted tuberculosis so doctors told Ichitaro to move to the country. That is when they started farming, about 1925. They grew strawberries, tomatoes and lettuce on 18 acres of leased land in the Florin area of Sacramento. The farm included a house and a dormitory for a seasonal crew of as many as 15 men. Yoneyo did all the cooking for her large family and the crew, and all nine children worked in the fields. When the family was evacuated in May 1942, they locked their belongings in the chicken coop. They were at Tule Lake until 1945. After camp the current tenants refused to return their belongings. Most of the family then worked as sharecroppers in Woodland. Everyone pooled their money to buy 12 acres of farmland in Rio Linda, CA, but they were not able to live as a family again. Eldest son Kaneo ran the farm and mostly grew strawberries. Ichitaro left the farm in 1955, and Kaneo sold the farm in about 1973.

Story as told by Elayne Shiohama and extended family: In 1917, Sanzo Uyeda sailed from Chikushino, Fukuoka-ken, Japan to San Francisco seeking a better future for him and his wife, Wasa, née Kawaguchi. He found work on a Caucasian family’s farm in Cutler, California. Wasa and Sanzo had two girls and two boys, starting with Mitsue, my dad Nobuo (later named Jimmie by a neighbor who couldn’t pronounce Nobuo), born June 17, 1921, then Kimiye, and lastly, Joe. As a youngster, my dad accompanied his father in many trades, including truck farming and running a pool hall in Lindsay. They farmed the area until WWII, 1941. Sanzo was torn away from the family when the FBI sent him to a prison camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico due to his membership in a kendo club. The daughters, married with families of their own, were interned, but Dad took his mother and little brother to Brigham, Utah. He worked on a sugar beet farm, in a cannery, cut the leather jackets for the US Bomber pilots, and also learned the building trade. Auntie Kimiye married a flower rancher and resided in San Diego County. Upon release of the internees, the Uyedas returned to California in 1946. Although faced with discrimination, Dad and Grandpa eventually found work in the building trade. Dad married my mom in 1947. She grew up on a tomato farm in Pomona. When Sanzo retired, he and Wasa moved to Lucerne Valley where his sons built a home. Two hours away from family, the ever busy Sanzo, built a koi pond and Japanese garden and grew Asian pears (nashi), for the Los Angeles markets for 15 years. He built a small “reservoir” but told the grandkids it was their swimming pool. He added a packing shed, refrigeration and taught Wasa, who never learned to drive a car, to drive the tractor. Stricken with cancer, Sanzo returned with Wasa to LA, where he passed away in 1976. Wasa remained in LA until her death circa 1986.

Kiyo (Kay) Ueda Hiatt (1926-2020) was a pioneer in the Florida Citrus Industry. She was one of the first women executives in the fresh produce business and wielded tremendous influence during her career. As one of the top sales agents of Florida citrus, she played a leading role in the tremendous growth of exports to Japan in the 1970’s to the 1990’s. Kay was a first-generation Japanese American citizen born in Fife, Washington. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Kay’s family was forced into an internment camp along with tens of thousands of other Japanese Americans. But she rose above the injustice and indignity of the long three years there to persevere and achieve success in the business world. Against great odds, she was accepted to Bucknell University soon after being released from the internment camp. After marrying Roy Hiatt, they moved to Florida where she began working at a citrus packinghouse grading fruit. Because of her insatiable appetite for learning, she queried employees in other departments at the packinghouse and gained a deep understanding about the overall operation. Soon, her curiosity paid off and she was asked to run the shipping office. That experience led to an offer to join the sales desk. In a few short years, she was promoted to sales manager. Kay was known for her keen intellect and love of language. She was a voracious reader and a talented writer. Kay was an iron-willed woman full of strength and stamina tempered by patience and self-sacrifice.

“Mr. Higashi was a farmer. He saw the wide prairies filled with waving grasses dotted with wildflowers. He decided it was the perfect place for a harvest of happiness.” So begins the story of the Higashi Family Farm in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Shiichi “Sam” Higashi immigrated from Hiroshima, Japan, to western South Dakota with his brother, Sanichi “Tom” Higashi, around 1916. They discovered the area after working during the sugar beet harvest. Sam returned to Japan to marry Kiwano, and after a short partnership with Tom and his family in Belle Fourche, SD, Sam and Kiwano moved to rented land in Spearfish, SD. Their children Clarence, Kenny, Mae, Jean, and Lily helped with planting and harvesting, providing the surrounding community with produce. Kiwano was widely known for her ability to raise strong, healthy greenhouse seedlings in the spring despite the frigid northern climate. Unfortunately, Sam passed away in 1940, but Kiwano and the children kept the truck farm going, raising sugar beets, cabbages, potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, and other vegetables. During WWII, Kenny enlisted in the military so that the family would be permitted to remain on the farm rather than face internment. From 1942-1946, he served in the 100th/442nd RCT, the only American of Japanese Ancestry from South Dakota in that unit. Clarence and Kenny eventually purchased the property, allowing Kiwano to remain in the family home until her death in 1978. Though the acreage is smaller, family members still reside there today. In total, the Higashi Farm operated for over 50 years. (Quotes and illustrations used with permission from the children’s book, “A Place for Harvest: The Story of Kenny Higashi”, by Lauren R. Harris, illustrated by Felicia Hoshino, copyright South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2022. www.SDHSPress.com)

In 1921, Kamenosuke Aoki along with other farmers went to Hellman’s Ranch to grow chili peppers for a chili pepper company who owned the land. The farmers lived on the land and were called “Hellmanites” because of how they lived and worked the land. The farmers would have to transport their crops from the farm to the chili pepper kilns dry houses in Huntington Beach to dry. Kamenosuke set up one of his ware- houses for the farmers to practice Judo and Kendo. Kamenosuke called this the “Aoki Kendo Hall”. In 1934 most of the farmers had left Hellman Ranch. Aoki was the last to leave but continued farming in the same area. Aoki was tired of growing chili peppers, so he decided to try farming in Oceanside CA. Kamenosuke and his son Iwao, decided to grow strawberries as their main crop. Growing strawberries flourished and was becoming successful until the war broke out. Aoki was taken to an internment camp in Poston, Arizona until the war ended. Aoki had entrusted all his land and equipment to a company that would take control while he was gone. The company misappropriated all his assets and equipment, and Aoki lost everything. After the war, Aoki returned to the Talbert area in Fountain Valley CA. where he farmed near Newhope and Warner Ave. His main crops were cauliflower, tomatoes, chili peppers and cabbage. He also farmed the property he owned and lived at on Beach Blvd and Ellis Ave in Huntington Beach until 1964.

In 1904, Kenji Abe, an ambitious 18-year-old from Kobe, Japan, embarked on a bold adventure to the United States enticed by the American Dream. His journey led him through the fertile landscapes, where he not only embraced the intricacies of farming but also found solace in Christianity after surviving a near death bout with pneumonia. Five years later, Kenji returned to Japan, married Shigeko Yasuda and immersed himself in the family rice brokering business. However, the allure of California's agricultural opportunities compelled him to return to the United States. Shigeko joined him a year later but without their first born child, Fumiko. Kenji’s parents kept the baby in Japan hoping she would be insurance for their return. In the midst of the Great Depression, the 1930s were a hard time for Kenji and Shigeko. They now had six American born children, Mary, Lily, Alice, Mollie, Franklin and Herbert, to raise. The family was blessed to be able to lease a small three room home with dirt floors. With no water or electricity, they cooked on a fire outside and used kerosene lamps to read at night. Kenji was able to work other farms and lease a few acres. He grew watermelons and tried sweet potatoes from plants given to him by a friend, Mr. Kishi. The depression made life tough for everyone, but with hard work, thrift, perseverance and a vision, the Abe family was able to save enough money to purchase a farm of their own. Consequently, discriminatory citizen requirements and the Alien Land Law, prevented them from becoming citizens and purchasing more property. As a result, they continued to save money and in 1939, when their daughter Mary turned 21 and was able to purchase land as a citizen, they purchased the 40 acre farmstead in Orosi, which is where Abe-EL Produce is still located today. The 40 acres was originally a grape vineyard, which in that day could have provided a decent living for most families. However, Kenji knew the land had more potential so he pulled out the older vines and replanted a couple acres with short crops like vegetables, tomatoes and melons. They also raised a few cows, chickens, pigs and rabbits. Since Kenji was still employed on other farms, Shigeko and their six children worked the farm before and after school and on weekends. They made friends with their neighbors, the Reimers and Silvas. Life for the Abes and other Japanese families changed dramatically on December 7, 1941, when they became the targets of severe prejudice and discrimination. They were all sent to an internment camp in Poston, Arizona. Before the family was relocated to Poston, Kenji asked a lawyer to draw up a formal legal agreement to lease their land to their neighbor, Tony Silva. Tony was an honest man and took good care of their property. However, when they returned from Poston they found that their home was leased to another family. They were forced to honor the lease and went to live elsewhere for six months. Being back home was not what they expected, life was filled with racial discrimination and resentment by the community. Despite the challenges, the Abes continued in farming and in the 1950s, Frank and Herb started packing their produce under the partnership name of Abe and Abe. Unfortunately, the Abe brothers found it difficult to find a market for their agricultural products. With the help of their friend Adrian Marquez as an interpreter, Frank moved to Mexico to grow tomatoes for a two year agricultural adventure. Upon returning to California, the agricultural economy was booming and with their hard work, Frank and Herb began to reap the fruits of their labor. In the 1960s, brothers Frank and Herb formed Abe-EL Produce. Along with Frank’s wife, Taye, and partner Clifford Rolland, they expanded the business as growers, packers and shippers. Frank inherited Kenji’s entrepreneurial vision and diversified the farming business to grow grapes, peaches, nectarines, tomatoes, melons, citrus, a variety of vegetables and even pistachios. All year round, there was always something to harvest. Frank’s mind was always thinking about how to increase production, trying other varieties, or another business venture. In the 1980s they expanded their business to the retail market and opened up Abe-El Ranch Market in Visalia. Through the years, Frank and Herb’s children, the Sansei generation, spent many hot summers working on the farm or in the packing house. In the 1990s, Herb’s son Duane Abe, Frank’s daughter, Kelly Abe-Hayashi and Frank’s son-in-law, Peter Mesias, joined the business and Abe-EL Wholesale became another facet of the company. Abe-El Wholesale provides fresh produce to local schools, government agencies and restaurants. At that time, it was common to see the Yonsei generation of Abes making boxes, palletizing, packing fruit, delivering produce or sitting at a farmer’s market or fruit stand selling farm fresh produce. Despite many challenges over the years, the Abe family has thrived, The Abe-El label has continued to transform to the needs of its customers. In 2016, the family introduced its Valu-ABE-EL produce boxes and began offering fresh produce directly to consumers at a reasonable price. The delivery of Valu boxes filled with fresh produce directly to the doorsteps of its customers during the COVID 19 pandemic was a blessing to many. This innovation brought them closer to the community and bolstered their reputation as a reliable source of quality produce. In 2021, Abe-El was the honored recipient of a Family Owned Business Award by the Business Journal and as Business of the Year by the Cutler-Orosi Lions Club. Though Kenji, Shigeko, and their children have all passed, the Abe family legacy lives on through its descendants who continue the family business with hard work, faith, and vision. Today, Abe-El is in operation under the capable hands of Kelly Abe-Hayashi. Taye, at 88 years old, still contributes her time and moral support by going to work daily. The Abe family legacy embodies resilience, gratitude and determination in the face of adversity, symbolizing the enduring spirit of the original American Dream. Abe-El Produce - Orosi, CA can be found on Facebook and Instagram and Valu-ABE-EL produce orders can be placed through their ABE-EL.com website.

In the late 1950’s a small farm was started in the Westminster area of Orange County, CA. It was a farm consisting of three families. it was made up of the Nakatani family, Hashiba family and the Kayano family. It was known at the time as NHK Farms. As the families grew and got older they eventually split into three separate farms, Nakatani Farms, Hashiba Farms and around 1970 Kayano Farms was started by Hajime and Noriko Kayano. Hajime’s family came from Okayama, Japan while Noriko Nakatani’s family were from Hiroshima, Japan. Coming to the United States by way of Seattle they eventually settled in Downey, CA. WWII came and they were interned in Rowher, Arkansas. Kayano Farms was based in Westminster, CA but had plots of land that they worked in Garden Grove, Stanton, and Riverside. Growing primarily leaf lettuce the operation eventually downsized and opened a roadside stand at the Westminster location. The farm and roadside stand stood until 2011 before it was permanently shutdown .

Toyoaki Ohara was born in Japan on December 7, 1903. He came to America at the age of 16 and worked as a gardener for Fox Studios. When he saved enough money, he married Teruko Kuboyama in 1934. In the 1930s they started to grow flowers in Inglewood, CA. When WWII started they were put in a concentration camp in Rohwer, AK. When the war was over, they returned to California and had to start over. They started growing flowers in Harbor City, CA on leased land. Here they grew stock, aster, and lochspur. Toyoaki and Teruko Ohara had six children – Sachiko (Susie), Toshiaki (Tom), Yoko, Teruaki (Ted), Etsuko (Patsy), and Masaki (Roy). In 1950 the family bought some land in Orange County and started to grow chrysanthemums under cheesecloth, and later in plastic greenhouses. In 1968 brothers, Tom and Ted, bought the flower business from their dad and leased his property while they looked for their own land. In 1979 Tom and Ted bought 10 acres of land in Anaheim, CA. Here they built 250,000 sq ft of steel greenhouses and a few saran ones and grew chrysanthemums, china, pom poms, and spiders all year round. They had a side crop of stephanotises, myrtle, and ivy. Even though Tom and Ted owned the business, it was still very much a family affair. Grandma, Susie, and Barbara (Ted’s wife) worked on the farm. Grandpa and Grandma lived in a house on the property (Tom lived in a separate house on the other end). Ted took the flowers to the Southern California Flower Market three times a week. They farmed on this land until 2004 when they sold their property under imminent domain to the Orange County Water District and were forced into early retirement.

Matasuke Fukuda was born in 1875 in Hakushima, Hiroshima, Japan. His Father Senjiro Fukuda was a ’Sea Lord’ Naval Commander for Lord Asano. Matasuke married Toki Nakamura and moved to Auburn, Washington to begin his life as a Dairy farmer in 1914. They had eighty cows on one hundred and eighty acres of land, corn crops, smokehouse for fish and a home for their eleven kids. The kids and family worked hard everyday milking and feeding the cows. Most of the sisters did not enjoy making cheese, milking cows early in the morning but they all enjoyed ice creme. In 1929 some racist neighbors cut their fertilizer and it killed the corn. The cows had no food so Matasuke was forced to give up the dairy farm, pack up all the kids, cars and migrated to California. Some of the kids settled in San Francisco, Fresno and Los Angeles. In 1933 Matasuke returned to Japan and built twenty-eight homes for families with children. While in Japan he experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He survived the blast as his house collapsed but left a small air pocket for him to survive. His love for family and compassion for people will be his lasting legacy.

Henry Takahashi graduated from Garden Grove High School and began strawberry farming in Garden Grove in 1964. A son of a farming family who grew various vegetables in Cypress, he concurred with other farmers that the most profitable crop to grow in Garden Grove, because the soil and temperature were both right, was strawberries. Not having any background in strawberries, Henry turned to Paul Murata for guidance, and within a year, Henry was a successful strawberry farmer. Henry says farming has changed through the years. As a farmer, he was not just a grower, but also a mechanic, carpenter, truck driver, horticulturist, pesticide specialist, welder, truck driver, human resource manager, accountant, and more. Henry Takahashi retired from farming in 1972 and now resides in Fullerton. The family has many stories to tell, such as actor James Colburn's mother lived over the fence ®gularly bought strawberries to give to her son. Their farming days were full of many wonderful memories.

Strawberry farming meant a steady income for Roy and Nancy Mitsuuchi, who began farming strawberries in Santa Ana in 1963. The Mitsuuchi found that the sandy soil was ideal for strawberry farming and eventually all their farming was switched to strawberry growing. Prior to strawberries, the Mitsuuchis farmed beans, celery, cauliflower, and tomatoes. The strawberries the Mitsuuchi harvested by the efforts of family and migrant workers were sold at their stand, to various restaurants and to the co-ops.

Haruki and Shizu Sakamoto began strawberry farming in Garden Grove in 1961, while continuing to work on the Fountain Valley farm of their relatives Paul and Hatsuye Nagamatsu. The Sakamoto farm in Garden Grove was small and was handled by the family and a couple of migrant workers. For over 30 years, Teruko Shimoda drove from Los Angeles every weekend to help the family stand (see photo below). In 1977, Haruki moved to Yorba Linda and continued farming until 1995.

After World War II, Masajiro Kotake returned to strawberry farming in Norwalk. Over the years, Masajiro began accumulating land and expanded the strawberry farm. The height of the Kotake strawberry farming came in the early 1980s with their farms in Orange, Los Angeles, and Ventura. In 1960 the Kotake brothers joined Naturipe Berry Growers Association as charter members. Strawberries were a good source of cash income and held high retail prices at the stands. Strawberry farming provided a comfortable life for the family but farming required everyone to pitch in and help from preparing boxes with baskets to picking strawberries. Strawberries were a good “mix” as it was a “winter” month crop between the tomatoes and other crops.

Nobu and Masako Matsumoto came to the U.S. in February, 1922. He was 18 years old and she was 17; both from Tottori, Japan. They were farmers in Fountain Valley and Garden Grove, California. During WWII, the Matsumoto family was incarcerated in the Santa Anita Assembly Center and the Poston Camp in Arizona. From 1922 to 1932 they had five sons; Key, Tak, Terry, Hiroshi, and Fred or “Freddy;” during the Korean War he served in the U.S. Army, 3rd Infantry Division, from 1952-54; he became squad leader of a mortar platoon and returned as a decorated sergeant. Soon after, brothers Fred, Terry and Hiroshi began farming in Niland, California, near the Salton Sea. In 1959 they built a packing facility, North Shore Produce, Inc., with specialized equipment for handling cherry tomatoes. Fred, a talented inventor, developed and improved machinery to chill, wash, color-sort, dry, wax, and convey the fruit in baskets. A grower’s son who worked with the brothers recalled one of Fred’s inventions: “a planter with seed hoppers capable of planting four rows of tomato seeds from the back of a tractor plow attachment! ….Another ingenious idea was to use airplane propellers to blow away the frosty winter morning temperatures in the desert, thus helping the tomato plants survive the frigid cold.” The three brothers helped popularize the cherry tomato through growing and shipping their “Mr. Tomato” brand, until bad weather and a voracious pest ended their operations in 1965. Fred returned to work with his parents and brothers Key and Hiroshi, running the Exotica plant nursery in Fountain Valley. Fred continued to create and refine machinery and devise equipment to remove large trees from the ground for transplanting. He became adept at the trimming technique need for cultivating black pines and Hollywood junipers, trees for which he was best known. He helped specialize in niwaki (garden trees). After his parents passed, the nursery became Fred’s. The family continued to gather there and enjoy his delicious persimmons, avocados, and sweet grapefruit. The nursery ran from the mid-60s until recently. Condensed from Rafu Shimpo Newspaper and Eileen Aiko Matsumoto

Oda Nursery started in Westminster, California by Issei Harunori (Harry) Oda and his Nisei wife Mitsuko (Mitsy) in 1958. Their first crop was field grown pansies on 2.5 acres of land at Bolsa Avenue and Bushard Street. Soon they added a flower stand, grew Junipers in containers and added more varieties of landscape plants to meet the demand of the Orange County home construction boom. The wholesale nursery concentrated on growing shrubs, trees, vines and groundcover for retail nurseries, landscapers and Kmarts. The motto “Watch Us Grow” reflected the business. Harry Oda was a good planner and bought more land adjacent to his original site. He also sought out growing grounds and in 1962 was one of the first to lease land from Southern California Edison. By the late 1960’s there were 7 growing grounds in Anaheim and Huntington Beach under the power lines and 17 acres at the original Westminster location. After the nursery maxed out of space, Harry looked to lease 250 acres from Rancho Mission Viejo in San Juan Capistrano. In 1978 the entire operation consolidated down south along with all the homebuilders. The 1970’s and 1980’s were robust years and the demand for plants increased across the country. The mild weather allowed Oda Nursery to grow a broad assortment of plants for different regions of the country and sales to chain and warehouse stores kept Oda Nursery’s shipping docks full and busy. After a heart attack in 1979, Harry passed the nursery to his son, Ken who had been working there most of his life. This transfer gladdened Harry since he felt his broken English hindered his ability to do business. Harry continued to pursue his real estate, horse racing and golf interests until he passed away in 2016 at the age of 91. Ken continued running the business until 1997 when Oda Nursery was sold to Color Spot Industries from San Diego. Oda Nursery employed 125 full time workers, produced 2,000 product combinations, shipped nationwide, had 20 acres of shade houses, 100,000 square feet of greenhouses on over 200 acres of land. Much of Oda Nursery’s success is attributed to the amazing timing Harry and Mitsy experienced during the entire 40 year span, having employees and customers who supported the business, and hard work to pursue their dreams.

Growing up on a sugar plantation shaped the life of Jack Gushiken. He was born in 1939 in Kilauea, Hawaii. Like his nisei parents Tokumatsu and Kikue Gushiken, Jack started working for the Kilauea Sugar Company (a C. Brewer subsidiary) in 1957 and became an irrigation specialist. That same year, he married Sharon Kawasaki and they had three children Lynne, Clyne, and Lee. After Kilauea Sugar closed in 1971, Jack worked for the Olokele Sugar Company in Kaumakani. Later in the 1970’s, Jack received two international assignments from C. Brewer. His first assignment was to Al Amarah, Iraq, and second assignment was to Shush, Iran. While abroad, he oversaw the irrigation systems and training of local villagers to cultivate sugar cane, sugar beets, alfalfa, wheat, and cotton. In 1978, Jack returned home to work for Kilauea Agronomics, another C. Brewer subsidiary. Initially, Jack oversaw the development of an aquaculture operation which raised freshwater prawns for local restaurants. When Kilauea Agronomics switched to guava production, Jack helped design and cultivate a 500-acre orchard known as Guava Kai which produced guavas year-round and provided purée to companies such as Ocean Spray, Tree Top, Minute Maid, and Motts. Guava Kai even had an on-site gift store featuring guava products and merchandise. In his free time, Jack also experimented with grafting, and after hundreds of seedlings he patented a new variety of guava, the Gushiken Sweet (HPSI 26). After C. Brewer closed in 2006, Jack became an advisor to the Wai Koa Plantation, which featured greenhouses with hydroponics technology, and Common Ground, which demonstrates regenerative farming practices. Even after his retirement in 2021, Jack continued to advocate for Hawaiian agriculture. He strongly believed in buying from local farmers so residents could benefit from the freshness and nutritional value of locally grown produce.