Tomooka Brothers Farm

The Tomooka family immigrated from the farming village of Kumamoto in Japan. Toyokichi came to America in 1903 and Toyokuma Tomooka in 1906. Toyokichi moved to the Santa Maria Valley by 1907 and Toyokuma followed. They both worked in the sugar beet fields for Union Sugar in Guadalupe making $10.00 per week and saved enough money to eventually lease 300 acres in Oso Flaco. They both saved enough money to request picture brides from Japan as well.

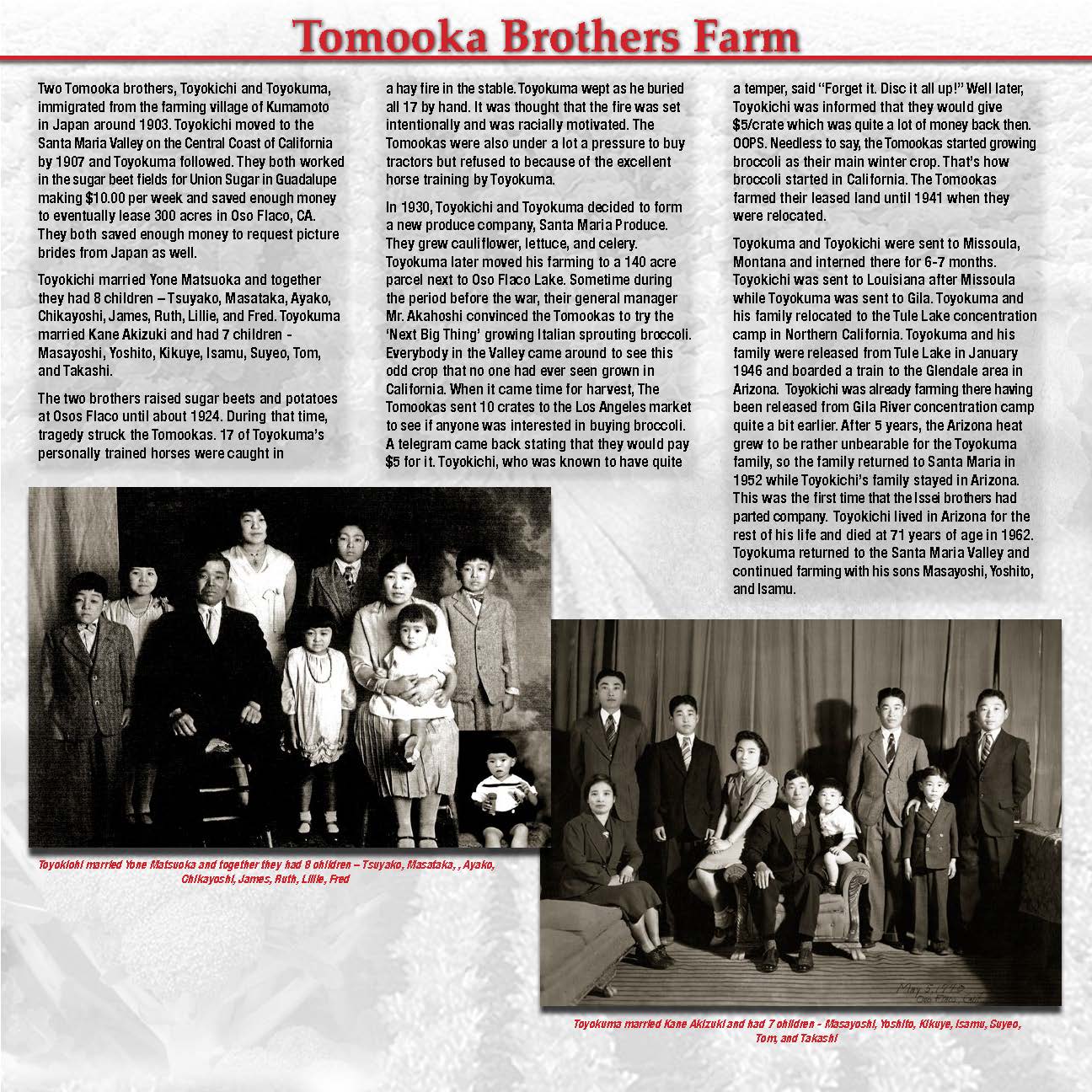

Toyokichi married Yone Matsuoka and together they had 8 children – Tsuyako, Masataka, Ayako, Chikayoshi, James, Ruth, Lillie, Fred. Toyokuma married Kane Akizuki and had 7 children - Masayoshi, Yoshito, Kikuye, Isamu, Suyeo, Tom, and Takashi.

There the two brothers raised sugar beets and potatoes at Osos Flaco until about 1924. During that time, tragedy struck the Tomookas. 17 of Toyokuma’s personally trained horses were caught in a hay fire in the stable. Toyokuma wept as he buried all 17 by hand. It was thought that the fire was set intentionally and was racially motivated. The Tomookas were also under a lot a pressure to buy tractors but refused to because of the excellent horse training by Toyokuma.

Around 1924, due to the Alien Land Law of 1913 and a revision in 1920, immigrants were not allowed to lease land anymore. So Toyokuma’s family moved to Avila where they helped grow bush peas in Shell Beach. It is unclear where Toyokichi’s family moved to due to the Alien Land Law.

In 1930, Toyokichi and Toyokuma decided to form a new produce company, Santa Maria Produce with Mr. Karasuda and Mr. Fujimoto. Mr. Ted Akahoshi was the Sales and General Manager who then hired Ken Kitasako, a Stanford Graduate and an Issei, a second generation Japanese American. Because of the Alien Law act of 1920, Mr Akahoshi put the farm leases under Ken’s name so the Tomookas could lease the land for farming. They leased land that is below the Nipomo bluff on Riverside Road from the Donovan and Souza families. There they grew cauliflower, lettuce, celery. Toyokuma later moved his farming to a 140 acre parcel next to Oso Flaco Lake owned by the Enos family. It was overgrown and wild with willow, weeds and junk but Toyokuma made that prime farming land. Toyokuma bought his first tractor in 1937, a McCormack model 35. The Tomookas farmed their leased land until 1941.

It was during this period that GM Akahoshi brought some seeds from Chicago. Italian Sprouting Brocolli. It was called that because they were going to market it to the Italian community in Chicago. Toyokichi started growing about 4 or 5 acres as a trial basis. No one in any of the farming communities in California had heard of or grown broccoli yet. Mr. Akahoshi claimed “It is going to be the ‘next big thing’. We have a market in Chicago if we cant sell it in California”. Everybody in the Valley came around to see this odd crop that no one had ever seen grown. When it came time for harvest, The Tomookas sent 10 crates to the Los Angeles market to see if anyone was interested in buying broccoli. A telegram came back stating that they would pay $5 for it. Toyokichi, who was known to have quite a temper, said forget it. Disc it all up! Well later, Toyokichi was informed that they would give $5/crate which was quite a lot of money back then.” OOPS. Needless to say, The Tomookas started growing broccoli as their main winter crop. That’s how broccoli started in California.

During the 1930’s, Depression or not, the vegetables were being grown, harvested, packed, and loaded onto railroad cars to cross the country. The produce going to Los Angeles was by truck. During the late 1930’s, the Tomookas sometimes didn’t have the money to pay the rent. Most of the time, landlords were understanding because they knew that farmers were doing their best and it was not their fault that the market was off. During this time, Santa Maria Produce had gone into heavy debt, similar to what other companies were going through. SMP owed money to places like the ice company who kept advancing them ice. They also owed money to a shook company in San Francisco. Shook was board used for making crates. The method of packing vegetables was also beginning to change over to packing them into ready made crates.

Around 1938, just when things were looking especially grim, things took a turn for the better for the farming community. By the end of 1940 sales started to pick up and SMP was able to get out from under some of their debts.

Ironically enough, the good fortune coincided with the beginning of WWII. But as history would tell it, life was going to deal another blow. The bombing of Pearl Harbor on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, sent the Japanese-American community into turmoil and upheaval. Around 11:00/midnight of that day, the FBI arrived at the Tomookas house in Oso Flaco. They emptied Toyokuma’s desk and put all of the papers into a duffel bag and took Toyokuma from his home and family. The two youngest children, Tom who was 9 and Takashi who was 5, and Kiku were living in the house with their parents, but the older boys were living in another house on that same property. The FBI went into that house as well and searched the premises with flashlights. One of Toyokuma’s sons, Suyeo, who was 15 years old, and cousin Mitsuki were sleeping when they got woken up first by the FBI and wanted to know where Grandfather was. Details get cloudy after this, but Toyokuma was taken from his home and family, and for about a week, no one knew where her was. Somehow they learned that he was in the Santa Barbara County Jail with about a dozen other Issei. So Kane and Massey drove down to SB and were led to the jail. Very shortly after they met with Toyokuma, he and Toyokichi were sent to Missoula, MT and interned there for 6 - 7 months. Toyokuma and his family were able to exchange letters, however all mail received was opened and censored. Toyokichi was sent to Louisiana after Missoula while Toyokuma was sent to Gila.

So while Toyokuma was in Missoula, MT, Masataka, Toyokichi’s oldest son, who was about 24 or 25 at the time, and Toyokuma’s eldest son, Massey, 21 years old, took over the farming operations of their respective ranches. They had workers to help them out. Their other siblings were still going to school during the week and would work on the ranch during the weekends. Everyone pitched in to help. Masataka oversaw the harvesting and shipping to the packing shed.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Issei could not live near the ocean within so many miles. And since Grandma Kane was Issei and living in Oso Flaco, she had to move inland to Guadalupe and stay with her relatives, the Oishi family. She took Takashi with her. The rest stayed in Oso Flaco. Kikuye cooked for them all. Toyokichi’s wife, Yone, and their youngest son, Fred, also went to live with the Oishi family.

Roosevelt’s proclamation 9066 to evacuate all Japanese from the coasts to the interior was announced. This included Issei and Nisei, Japanese immigrants and their American born children who were citizens of the United States.

Some provisions needed to made for Santa Maria Produce, since all of the principals were Issei and Nisei. Leo McMahon proposed that Puritan Ice Co. would act as trustees for Guadalupe Produce under the Aratanis, the Minami’s and Santa Maria Produce and operate all three operations for the the duration of the war. GP had about 4500 acres, the Minamis about 5000 acres, and SMP had about 1500 acres, totaling around 10,000 acres.

Without the trust, they would have been assured of losing it all, crops, equipment, everything. With this trust, at least they might have a chance. So by day they shipped vegetables; by night the principals from the Minamis, GP, and SMP worked until 2:00 a.m. to work out this deal with Puritan Ice and the attorneys to form a trust called California Vegetable or Cal Veg.

April 29, 1942, all of the Japanese on the Central Coast were sent to the Tulare County Fairgrounds in the San Joaquin Valley. From there, the Tomookas and others tried to communicate with the packing shed. They obviously were prohibited from leaving the Assembly Center. They were not allowed to use the telephone and there was no way to communicate. Cal Veg’s secretary/bookkeeper did her best to keep in touch, but she had her own work to do for Cal Veg as well.

The operations kept going as it was until a time when Leo McMahon, the attorney, said that Puritan Ice wanted to buy all three companies out. The principals of GP, Minamis, and SMP had their ideas of what a fair and equitable buy out would be, but of course, Cal Veg’s ideas were a lot lower. They felt that the way things were going, the best they could do was to grab what they could then and do the best they can. And so Santa Maria Produce, the Minamis operation, and Guadalupe Produce was sold.

The plan after that was to then later go to Uncle Sam to get compensation for the farms because after all, the government put them in camp. A very prominent Los Angeles law firm specializing in civil rights later took on the case for SMP. Masataka had worked out the details of case with this LA law firm. In the end, SMP was compensated, though not sure of how much or any of the details.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the order that all Japanese had to evacuate the coastal areas, Masataka and Massey were advised they could go out to Blythe to farm instead of going into the concentration camps. The Blythe area was beyond the No Japanese boundary. Several Japanese relocated to different parts of the country such as Utah and Colorado. And remember, most all of the Issei were already interned elsewhere, so their families were on their own. So Masataka and Massey planned to move their families and a few other families to Blythe to farm. They picked up materials at the junkyard to make trailers into which they could put their belongings on their trip out to Blythe. They worked on those trailers until late at night for many nights. Then about a week before the evacuation date, they felt that it would not be fair for only them to leave, leaving the other SMP families behind, so they ultimately decided to forget about going to Blythe and instead they were evacuated to Tulare Assembly Center together as a group.

As with every other Japanese family in California who were evacuated, they left all of their belongings behind taking only that which they could carry. They had been informed that they should burn old photographs of relatives and friends in Japan and anything that was connected to Japan.

April 29, 1942 the Japanese were put on Greyhound buses to Tulare County Fairgrounds. That was the first time that Massey and his siblings had ever been on a Greyhound bus. This was the assembly center to which all of the Japanese on the Central Coast was sent. The Tulare Assembly Center was fenced in by barbed wire and guard towers. The Japanese lived in barracks, some were forced to stay in the horse stables, but as Massey, recalled, “We were lucky. We had barracks.”

In the fall, they were sent by train with curtains drawn, to the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona. When they arrived, the camp was not yet finished. Sewer lines and pipe lines were still open. It was dusty, windy, and hot. No photos during this time - cameras weren’t allowed until later. At Gila, Toyokuma was reunited with his family.

While Toyokichi was still interned in Louisiana, his wife, Yone, became gravely ill in camp. After getting all of the necessary permits to leave Gila, Masataka took a train to Louisiana to bring his father back. Masataka had to have guards accompany him on his journey, and he was required to render their pay as well as pay for their train fares. Yone passed away at the age of 48 only one day before Toyokichi arrived at Gila River. Sometime later, Toyokuma and his family relocated to the Tule Lake concentration camp in Northern California.

After the Toyokuma Tomookas were released from Tule Lake in Jan 1946 with only about $150.00 that the government gave them, they boarded a train to the Glendale area in Arizona where Toyokichi was already farming having been released from Gila River concentration camp quite a bit earlier.

The Toyokuma Tomookas ended up living in what was little more than a shack. When it rained, the roof leaked so badly that the ceiling fell down. It rained hard and thundered a great deal in Glendale. Eventually, they were able to purchase 40 acres under Massey’s name as Massey was old enough to do so. They grew lettuce and canteloupe. They worked day and night to buy one tractor.

After 5 years, the Arizona heat grew to be rather unbearable for the Toyokuma Tomooka family, and with Massey’s insistence, the family returned to Santa Maria in 1952 while the Toyokichi Tomooka Family stayed in Arizona. This was the first time that the Issei brothers had parted company. Toyokichi lived in Arizona for the rest of his life and died at 71 years of age in 1962, but Santa Maria became his final resting place.

When the Toyokuma Tomooka family returned to Santa Maria, they were touched and overwhelmed to be given a welcome home party by their Santa Maria Valley and Arroyo Grande friends who had already returned to the area.

Toyokuma and Massey got their start again in farming in this area through the generosity and assistance of Mr. H.Y. Minami. Mr. Guerrera, a landlord, had some land to farm and asked Mr. Minami to farm 90 acres on Riverside Rd. in Nipomo. Instead, Mr. Minami let Toyokuma and Massey start farming those 90 acres which were then leased under Massey’s name.

In the meantime, Toyokuma’s wife Kane’s American Dream came to fruition. From having moved from rented home to rented home ever since her arrival in the U.S. she was able to finally call a house on the eastside of Santa Maria, her home in 1953. Toyokuma was 65 years old and Kane was 53 at the time. After Toyokuma lived in the US for 49 years and Kane for 35 years, they earned their citizenship at the swearing in ceremony in Santa Barbara on Dec. 15, 1954.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Toyokuma and Massey were beginning to expand their farming operations in Nipomo to 450 acres, internally known as ranches 1 - 6. These leased properties comprised of the Guerra ranch, which is now owned by the family, the Amoral ranch, the Souza ranch, the Canada ranch, and Joe Souza ranch. The ranches were numbered to help distinguish the different plots that needed to be fertilized or inspected. Prior to numbering the ranches, the pest control operators made mistakes and sprayed the wrong field.

Two of Toyokuma’s sons, #2 Yoshito and #4 Isamu, joined the farm as acreage increased. Yoshito was mainly in charge of the tractor work and irrigation. Isamu’s primary responsibilities were cultivation and planting. Massey did the general managing of the farm, pesticides, and the harvest. Toyokuma was the father, and was generally overlooking the whole operation. As Massey, Yoshito, and Isamu’s sons and their cousins grew up, they, too, helped on the farm on weekends and during the summer.

The farm operations expanded to about 1000 acres being farmed which included 100 acres on division road which was bought from Bud Gracia, 160 acres leased from Sutti, 200 acres across from the Guadalupe cemetary bought from Mrs. Donovan, and 300 acres leased from Ralph Mareti, near the Guadalupe beach area.

Toyokuma taught Massey all he needed to know about growing lettuce and broccoli. Massey also learned a few of Grandfather’s superstitions along the way one of which are - Never start the first harvest of the year on a Friday. Never conduct major business on a Friday.

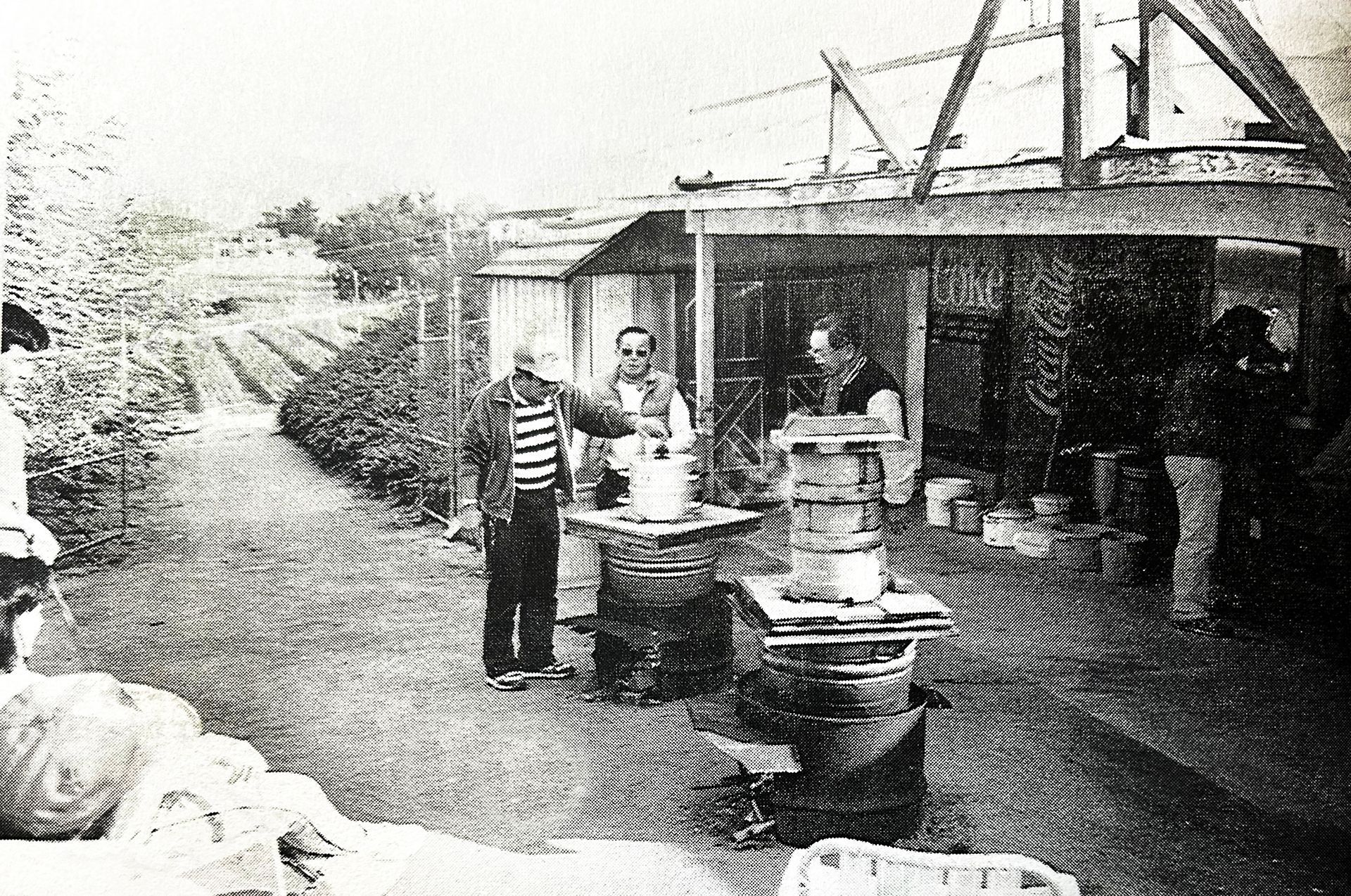

Tomooka Bros. grew lettuce and broccoli which remained as their two crops throughout their farming years. Lettuce was planted during the spring and harvested during the summer. Harvesting was usually between April through the end of November.

In 1970 two unions, the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee headed by Caesar Chavez and the Teamsters Union were attempting to organize the farm workers in this area. The fields at the Tomooka Bros. ranches, identified as a major grower along with others in the area, were targeted and picketed by the UFWOC, Chavez group. The fact that Tomooka Brothers were Japanese Americans--started by immigrants--was ironically ignored. Their operation was subject to demonstrations, vehicle vandalism--sugar in the gas tanks--, and their fields were flooded at night by irrigation equipment being turned on. As a response to protect their business assets, from July - November 1970 two security guards were hired to patrol their office and fields round the clock. UFW became the fieldworkers choice.

Toyokuma worked on the ranch until he suffered a stroke at the age of 78 at which time he was confined to a wheelchair. He passed away in 1972 at the age of 82. Kane passed away in 1994 at the age of 94.

The Buddhist Church played a large part in Toyokuma’s and Kane’s lives. They gave generously to the church. Toyokuma was also one of the Issei who participated in the groundbreaking ceremony of the then new Buddhist Church on Obispo St. in Guadalupe. Likewise, Kane was very involved in the Fujinkai, the women’s auxiliary group of the Buddhist Church.

Toyokuma also was a strong contributor to Marian Hospital, now Marian Medical Center, in Santa Maria. Tomooka Farms supported many local non-profit organizations. Loving baseball as they did they naturally supported local baseball teams, from semi-pro to the small youth leagues. Toyokuma received two honors from the Japanese government for his contributions to agriculture.

Yoshito and Isamu retired in 1991. Massey bought them out and farmed independently until 1993. At this time, he became partners with Betteravia Farms. Massey grew the lettuce and broccoli, but Betteravia Farms did the harvesting and shipping. In 1995, he sold his business to Betteravia Farms and retired. In 1997, Massey was honored as Farmer of the Year at the Santa Barbara County Fair.

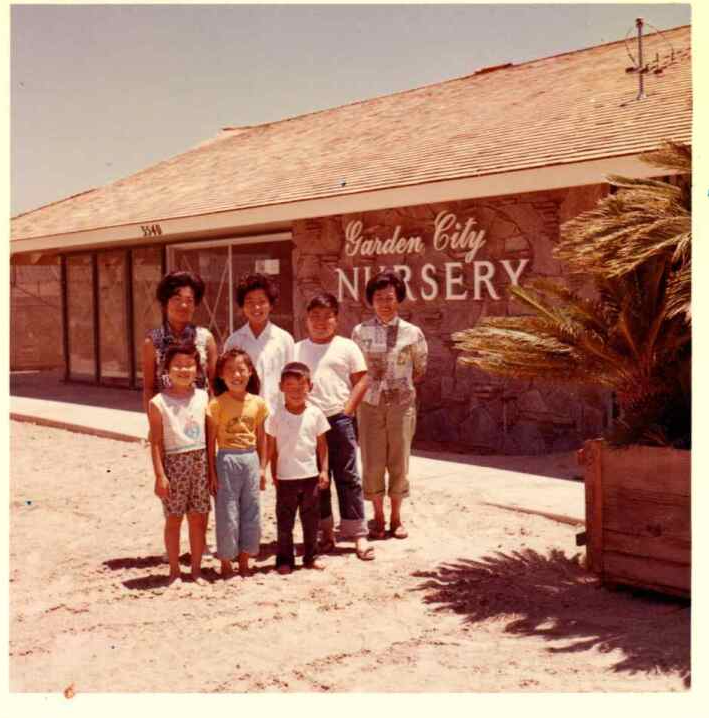

Toyokichi married Yone Matsuoka and together they had 8 children – Tsuyako, Masataka, , Ayako, Chikayoshi, James, Ruth, Lillie, Fred

Toyokuma married Kane Akizuki and had 7 children - Masayoshi, Yoshito, Kikuye, Isamu, Suyeo, Tom, and Takashi